Is Easter in fact Ishtar?

Analytically Reclaiming Folk Etymology!

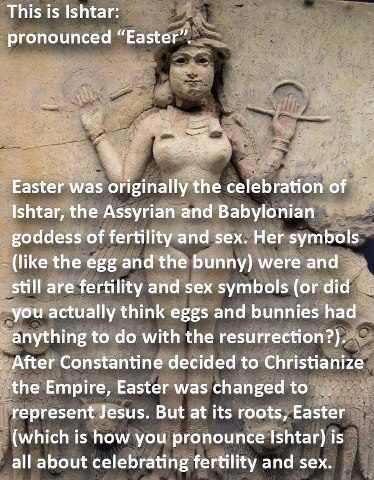

This is the season for one of these memes that spin religious knowledge. Though somewhat less wonderful than the Santa-is-Odin-memes (link: https://youtu.be/pgJ3TOC058o), the well-known meme identifying Easter with the Babylonian goddess Ishtar is essentially a similar kind of religious production of meaning.

The similarity between the words “Easter” and “Ishtar” has long been noted, (and weaponized). The mid- 19th century Scottish minister, Alexander Hislop used the similarity in his railings against the Catholicism. He claimed that the name of the holiday, “Easter” referenced the Babylonian goddess Ishtar and he thereby cast the Roman church as a whore of Babylon. For contemporary Pagans however, the similarity is fertile with meaning as they seek to enrich the Easter holiday through identification with a prehistoric Pagan figure. Here I just want to share a small afterthought as a challenge to all the philologically savvy people who voice hard judgements on those soft associations with which humans build or rebuild traditional holidays.

The string of thought was inspired by an individual I witnessed commenting in a discussion thread. This poster made what scholars call a “popular etymology” or "folk etymology", i.e. the attempt to “make sense” of a word through surface similarity rather than historical linguistics. He attempted to make sense of the goddess name Idun (from Old Norse Iðunn), but his proposal was rejected by scholars in the group. My argument here is that perhaps we should be a little bit more careful when we deny that sort of linguistic surface association by popular etymology as a valid way of producing religious meaning. In fact, I think it is a really important kind of religious thinking.

Specifically, the poster asked whether the Biblical fruit of life in Eden could perhaps be associated with the apples of held by the Norse goddess Idun. Also this similarity between myths and names has history. It was first observed by the mid- 19th century scholar Sophus Bugge who used it to dismiss Idun as an imitation of Christian myth. Well, Bugge’s theory was rejected, but the similarity hasn’t disappeared and in this Facebook group a discussion ensued where this Christian connection was denied as mythic food giving gods life is a rather common motif. A scholar in the thread rightly pointed out that the similarity in English forms of the names Eden [עֵדֶן] and Idun [Iðunn] is coincidental and that any claims that the two are connected are superficial “folk etymology”. In other words, there's no historic connection between these two words, even if they somewhat resemble one another in their current English forms.

Yet, is there no validity whatsoever in the poster's observation? Can meaning only flow between words when they are linked through exactly that kind of unilinear historical descent of the type that sees modern English Odin descending from Old Norse Óðinn which in turn is hypothesized to descend from Proto-Germanic *Wōđanaz. I am quite convinced that that meaning certainly flows through surface likeness and further, these likenesses may even be stronger and more religiously potent way of producing religious knowledge. It is such a surface likeness that the nifty meme makers of the Cybergarðr use to identify the Babylonian goddess Ishtar with the common English name for the Passover holiday, Easter, a word which is probably derived from the name of a goddess, Ēostre, just not a goddess with any known historical association with Ishtar.

Here is an example of such surface likeness from my own field research in the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé-religion, a syncretic cult of the West African orixá-gods, a wise priest once told me the following myth of the divine tree that binds heaven and earth together. This is a transcript of what he said:

In the beginning when the world was created, Olorun [God] descended and the orixá gods descended by the Iroko tree, the Tempo tree. “Iroko” is Yoruba and “Tempo” or “Dembu” is Bantu. [Yoruba and Bantu are different African languages]. They went down through this tree in order to come to earth. It is said that Iroko, or Tempo, is a mentally unstable orixá, a sort of unpredictable orixá. Tempo is like the weather [Portuguese: o tempo]. One moment the sun is shining, but in the next it will be raining. And therefore, it is said that he is a bit crazy [Portuguese: louco].

Note how this Candomblé priest not

only pans through different meanings of different names of the orisha.

He is also fully aware of the different unrelated linguistic origins

behind the different names, Loko and Tempo. He uses Portuguese

associations, Louco(crazy) and Tempo(time)

to describe the deity, but he is completely explicit that these names

are derived from superficial similarity from different words in entirely

different languages, Yoruba: ìrókò, and Bantu: Dempu.

Why

do contemporary Pagans often deny themselves access to this powerful

tool of religious knowledge-weaving? Why not empower ourselves

analytically to use this important tool for positive construction of

knowledge? This would seem logical from a couple of perspectives. In the

case of the fruit, the motifs are so strikingly similar that it is

probably safe to conclude that their root meanings are comparable, if

not the same. And if we allow ourselves the syncretism to expand our

understanding of Idun with the motif of Eden, then we are really

enriching this little known goddess with a mythic structure, that is

fundamental in our culture and which would therefore give Idun deep

recognition and cognitive anchors in our perception. This would

potentially yield mystical potency as well as intuitive recognition.

Similarly

the goddess Ēostre, the origin of the modern English word “Easter” is a

little known deity where as Ishtar is a well known, rich figure. Why

not let the inspiration flow?

Ēostre / Ostara in Romanticist imagination.

And what exactly is the argument to exclude folk etymology from being a religiously valid way to develop/construct religious meaning? I would like to hear it. As we saw with the Brazilian orixá priest, functional religion does create meaning in exactly this way! From an animist perspective, the associative process that identifies Ishtar with Easter is a perceptive fact, because the words are de facto similar. And from the animist perspective this similarity is not irrelevant, because a non-human subject such as the goddess Ēostre is predicated on flows of perception, so a perceived association with Ishtar could be seen as qualities pertaining to the non-human subject itself (Viveiros de Castro 1998). This means that the association to Ishtar is a characteristic of Ēostre in herself, not Ēostre as an irrelevant cultural symbol. No! A quality of Ēostre as a real subjective agent with whom we share reality. This implies that perhaps we are not really serving Nordic polytheism by rushing in with linguistic science and insisting on stigmatizing the capacity of Pagans and Heathens to form this kind of natural and meaningful identification.

I know that this very associative way of dialoguing affronts historical notions of how to establish knowledge. It is an identification that rests on surface similarity, not on historical identity. But what exactly do we have to work with instead? I regularly see historical linguistics applied in Indo-Europeanist etymologies induced from a string of half-known Iron Age scripts, through some gnostic sound development acrobatics towards some marginal meaning that may perhaps have existed somewhere around the Black Sea some 5000 years earlier. Is that supposed to be a better method for constructing contemporary religious meaning than saying that Easter is in a sense Ishtar? What exactly is the base of the assumption that only historical linguistic produces valid knowledge of the meanings associated with a figure, that the only valid association to the name Iðunn are prehistoric hypothetical roots like Proto-germanic *Iðunþiz, but the word Eden is not a valid association because it is something as disappointingly profane as contemporary English? I would like to hear strong arguments that the narrow etymological observation that Easter and Ishtar aren’t philologically related should necessarily be projected unto an entirely different kind of knowledge, i.e. the knowledge of the goddess Ēostre as a divine being, a subjective structure of perception, as a target of cult, as a protective spirit, as a participant in ritual, or as a religious agent.

However, if I am right about this, then how do we handle the conflict with our contemporary scientific base because Ishtar and Easter are indeed not etymologically cognate. As already suggested one way of looking at this is Animism. Animism claims that perception is inhabited by subjectivity and that we can identify gods and spirits with the structures of subjectivity in the perceived world. For instance, the Inuit deity Sea Mother is the personification, the subjectivity of the sea because the sea is such an important element of Inuit perception and life. She is dividuated—she becomes reaizedl through that relating and becomes a dividual, a related personhood.

A perceived association between between Ishtar and Easter consists of associative features of contemporary perception, and—for sure—the commonly disseminated meme above is founded on an unscientific kind of historicity. However, let us shift our perspective away from historical etymology, the question of whether Easter and Ishtar are historically related names. Let us instead look at perception. Then the identification appears rather more real, as an actual management of non-human subjectivity, than those rather speculative lines of origin back to pre-historic hypothetic languages. Names such as Easter and Ishtar may not be historically related, but they most certainly are linked through the oldest and most established principle of magic—likeness !. They sound similar to the contemporary speaker are therefore associated. From an animist perspective, the implications of this process is that subjectivity can grow in this identification: In other words, the goddess Ēostre can be meaningfully dividuated, 'made real through relation', by her association to the richly recorded and comparatively well-known goddess Ishtar.

If you were to translate into normal human language this Animist theory-speak about dividuation, and the subjectivity inherent to perception, then one way of formulating it could be to say that the goddess Ēostre actually likes or wants to be identified with Ishtar, because intention, wanting something, is implied in subjectity. And why shouldn’t she? This would deepen and expand her anchoring in occidental cognition, empower and enrich her through identification with a very rich and powerful figure. She would be given an expanded wealth of meaning and motifs with which to produce meaning in contemporary contexts. In other words, let us think twice before we implement the social weight of an academic voice in denying contemporary Heathens and Pagans folk etymology as a tool in realizing their deities.